I Stream, You Stream, We All Stream for…: Which Streaming Service is Biggest with Each Major Genre?

(PLEASE NOTE: An explanation of who we are and what we do is available at the bottom of this entry, in the form of a couple of links and a nifty video. Additionally, as this is a long entry, we have provided well labeled, easily comprehended and colorful charts, skimmed in mere minutes or less — for the reader on the go.)

What are you looking at above? What could it possibly mean?

We realize it’s probably rather self-explanatory, but indulge us as we explain further.

As you might have surmised, we’ve set out to demonstrate the diversity of StatSocial’s capabilities (check out the links at the bottom of this entry to learn more about us, and what we do), by sharing some of our metrics regarding the top music streaming services.

We’ve sorted through the mountains of data at our disposal, using the major commercial genres — basically, most of the prominent radio formats — to see which of the biggest streaming music services most appeals to the fans of each genre.

But first, not so much a history lesson, just a little background on how we as a people got to where we are with this entire area of commerce. We think this quick review ultimately helps one to better understand how findings such as ours are of crucial relevance to a marketer or a brand. This, particularly if the competition is not forthcoming with its own numbers.

This will not be our first trip to the streaming music well, as we’ll be digging deeper shortly; getting into artists, and labels, and explorations beyond the crust, and even the mantle.

For now, though…

They all laughed at Christopher Columbus

When he said the world was round

They all laughed when Edison recorded sound

They all laughed at Wilbur and his brother

When they said that man could fly

They told Marconi wireless was a phony

It’s the same old cry

As Ira Gershwin cited the skepticism met by history’s various visionaries, there was a time when many scoffed at the iPod. Its broad appeal evading more than a few of those short on vision. People regarded it as a niche item. While the reasons were numerous, two were primary; one, there was doubt that huge numbers of people had the desire to spend what was then a lot of money to carry 5,000 songs (or whatever the number was at the time) with them wherever they went. So, the product was for hardcore music nuts exclusively.

Additionally, for the first couple of years of its lifespan, it was Mac-compatible-only. So, to many the expensive little gadget was neat, but it was a luxury item, only appealing to a portion of what was at that time the Mac’s already limited market share.

Within a couple of years it and its accompanying software interface iTunes were Windows compatible, and sales exploded. You know the rest, before long a black turtleneck and jeans became iconic, and a lot of laughter turned to tears as those who could have bought Apple stock cheap counted the millions they left on the table.

Prior even to that, crucially, a student at Boston’s Northeastern University created a software platform he called Napster (apparently a nickname the software’s developer, Shawn Fanning, sometimes went by). Initially developed innocently as a way for the people in a single dorm building to share files with each other easily, it quickly spread out into the public at large, and people the world over were using it — with speeds which would seem ludicrously slow by today’s standards — to download music. This music very often included copyrighted recordings by major artists, and these users were amassing libraries of hundreds or even thousands of songs free of charge.

Some big names — most famously Metallica and Dr. Dre — tried to fight it, but it was bigger than they. It was bigger than the whole music industry, truthfully. They’ve literally just begun to come to terms with that.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/VIuR5TNyL8Y

The audio quality of mp3 — the audio compression that, in concert with ever increasing broadband speeds, made all of this possible — was maybe slightly better in sound than a terrestrial radio broadcast, and wasn’t even close to what a CD could provide. People hardly cared. It sounded okay, and it was free. Music on tap. The future had arrived.

Experts had been saying for literally decades that file compressions and internet speeds would shrink and/or increase exponentially to where this phenomenon was inevitable. Some of these experts worked for record labels (and film studios, but we’re not talking about that yet), but their bosses were thinking quarter to quarter, and this writing on the wall of which the tech soothsayers were warning them was still a ways off. Or so they thought. They’d cross that bridge when they got to it.

But the bridge came to them, and quickly. They had ample opportunity to get ahead of the issue, but instead when Napster came along, they were caught with their pants down. Other, faster peer-to-peer services followed, such as Kazaa, which additionally allowed for video sharing with relative ease (you could get an episode of a TV show in a mere 24 hours to 5 days).

(The Napster discussed above — which was a peer-to-peer file sharing platform — is not really the streaming audio service on the charts below. It is now the name of a service formerly called Rhapsody. They rebranded as Napster, as it remains a globally recognized name.)

Then BitTorrent came along, and truly the game was changed, as broadband speeds and computer processor speeds were increasing seemingly by the minute, and suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, as these things often appear, the fastest file sharing platform yet was unleashed on the world.

But this isn’t a history lesson, and there’s really no quick way to explain how BitTorrent works. But as many reading know, it made audio and video sharing faster than was ever believed possible.

I’ll cut this short here, though, and get down to business.

The point is that instead of figuring out a way to monetize the toothpaste that was out of the tube starting with Napster, the music industry’s initial solution was to target random illegal downloaders — traced via IP addresses, provided by ISPs — and sue them, hoping that by making an example of some college kid who just wanted to listen to Slayer, saddling him with a six figure fine and possibly even a criminal record, they’d put an end to this file-sharing chicanery.

While they may very well have had a legal leg to stand on, endless lawsuits of random people is hardly a sustainable business model, and illegal downloading continued unabated, with the sound quality of file compression improving constantly.

Apple rather brilliantly figured out that people would pay for downloading, if you provided a better quality file than the mp3, and did so at the right price point. $0.99 a song ($10 for most single albums, whatever the number of songs) seemed fair to millions of users, and for a long while iTunes’ music store was hugely successful, making the major labels money, while also making them look stupid for not having thought of this themselves.

Okay, you know all this. But we’re providing context. It turns out, most people love music, and love having access to a large variety of it. Both at home and while on the go.

Suddenly the “playlist” became a concept. The old mixtape of yore was more easily assembled, and took up much less space. “Shuffle” also became part of the vocabulary. While making selections randomly from the music available in your own private library, having no idea what song shuffle would play next was a bit like having your own curated radio station.

And of course, while a joke on HBO’s excellent Silicon Valley, bringing “radio to the internet” had long been promised by the experts as inevitable. Smart phones came along, and suddenly “mobile internet radio” was the next logical step.

The Google owned YouTube — where copyright law is observed in a very loosey-goosey way, and where generally they’ll let any old thing be uploaded, only taking it down when someone complains — became an invaluable source of hearing music for free. Whether out of print records from decades’ past, or the latest single by an indie band you read about in a music blog. YouTube, while a video site, also demonstrated the unstoppable demand for a wide variety of music at ones fingertips.

The initial wave of streaming music services actually included some of the big players — Amazon, Google, etc. But the hats they tossed in that first ring, went largely unnoticed.

Pandora presented the notion of “smart” internet radio. Licensing a vast library of music from the catalogs of the various major labels (Universal and Sony, etc.), you could create channels based on favorite acts or songs. If you liked Grim Reaper it would find other music that shared qualities with the music of Grim Reaper. Eventually you could then create a Grim Reaper channel, and save it. Whenever you were in the mood to rock out to what Pandora’s ever-improving algorithms had determined fit the Grim Reaper format, pulling from its ever-increasing library of songs, that sweet rock was just a click away.

A plethora of services sprung up — some deliberately catering to more niche audiences, some aiming for broad appeal — but around 2011, Swedish entrepreneur Daniel Ek’s Spotify, which had actually launched a couple of years prior in Europe, came to the states. It provided a free service with ads, and a subscription option without. It also boasted an easy integration with third party sources such as blogs, and most significantly Facebook and Twitter. This integration brought to Spotify a social element, making it easy to share your favorite songs and your carefully programmed playlists with friends. Spotify’s library was also huge, and constantly growing. (It now contains over 30 million songs, provided by labels both big and small.)

In 2016, though, it is not without competition. As Spotify became more and more how people, particularly young people, listened to music — hard copy sales virtually vanished, and even the purchase of audio tracks for download suffered — artists complained, justifiably, of the pittance they were receiving in terms of royalties. Only a fraction of what had long been the royalty rate for terrestrial radio play.

While the artists may have had a right to their anger, they had signed contracts years before that couldn’t have anticipated the technology. Some artists’ attorneys were shrewd enough to negotiate clauses that set a fair royalty rate for formats and technologies then not yet developed, but such deals were rare. Clauses of this nature are, of course, much more common now.

The labels were having a hard enough time maintaining their own bottom line, and being equitable never their top priority, they were especially not going to part with very much of the small amount they themselves were making; happy, as they were, to be making anything at all.

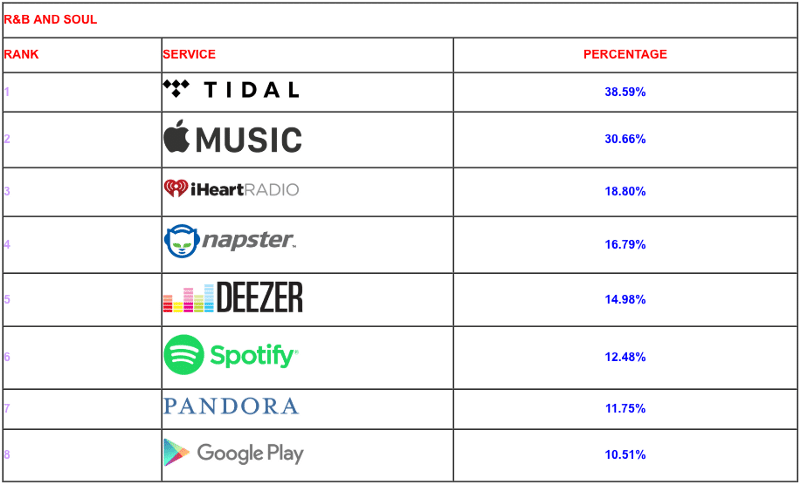

Then in 2015, Jay Z, the enormously popular rapper and successful entrepreneur acquired Aspiro, a Danish streaming service that boasted lossless audio and about a half million paying subscribers. He renamed the service, and re-launched it to much hype, as TIDAL. A subscription service exclusively, but one where Jay Z (Shawn Carter) and his equally powerful and successful wife Beyoncé Knowles could use their substantial influence to provide exclusive premieres of both audio and video, from the biggest artists of the day. And the aspect they hyped most of all, artists were paid a much more fair royalty rate; “artist owned and operated, and putting the artist first.” Or at least so went the concept.

At the initial press conference, a diverse assortment of music’s biggest names from Kanye West and Nicki Minaj to Daft Punk, Jack White, and even Madonna were presented as co-owners of the new “artist friendly” service.

“They all laughed,” as it were, but it’s been well under 2-years since the service was launched and it has over 4 million paying subscribers.

Spotify, still the king of the hill, has very real competition.

Apple opened the can of worms — in the public’s minds and hearts — and they themselves are now in the streaming audio game, with Apple Music. When Tim Cook and company acquired Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine’s Beats Electronics, to much fanfare and some head scratching, they soon thereafter shut down Beats’ subscription music service and launched their own explicitly Apple branded one.

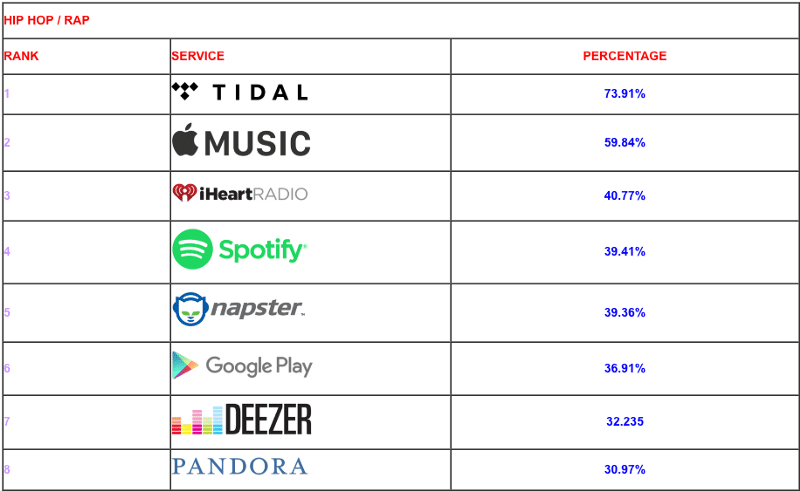

While each of the major streaming services boasts a diverse library of artists and genres, as the major labels (and many indies too) are all too eager to cooperate, as streaming audio has become their most reliably lucrative income source, some — as TIDAL does frequently — negotiate exclusives, of new records, or even entire artist catalogs. Beyond that, for reasons both obvious and easily explained, and sometimes due to causes requiring deeper digging (often answered in the data StatSocial has available), certain services are more popular with the fans of certain genres than others.

As is clearly and unsurprisingly the case, which you can see on the chart at this entry’s beginning, the top streaming service with fans of Hip Hop — its most high profile partner also being Hip Hop’s biggest name — is of course

As the streaming music revolution really began at the start of the decade. Predicted for years (as we’ve said) by those who understood where broadband and mobile technologies, as well as audio compressions, were heading, it wasn’t long before the winners of that first wave began to emerge.

While major players like Amazon (Amazon Cloud Player) and Google (Google Music) were among the first crop of names, their services at that time were more just music player apps that allowed you to access and catalog music files you had stored on their clouds. (Both are now in the game in a way more competitive with the true streaming services, Google Play, of course, included in this study).

The number of people who actually listen to Amazon Prime Music — launched in 2014 — is still largely disputed, and the service lacks access to the catalogs of many of music’s top acts, both past and present. In other words it is not yet the music equivalent of their fairly excellent Amazon Prime Video service.

But let’s leave the past behind for now, and dig into what the chart above teases. Which of today’s top streaming audio services most appeals to the fans of the top music genres.

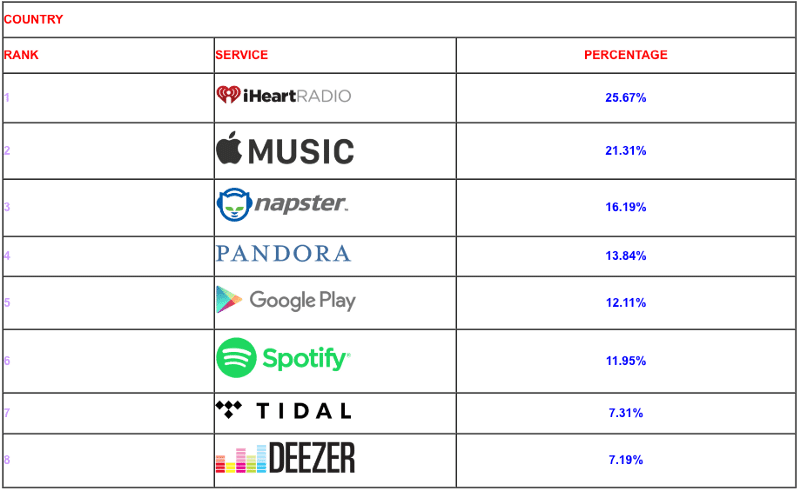

COUNTRY

Nashville has been extraordinarily grateful to its faithful, as they still overwhelmingly purchase their recorded music in hard copy. Good ol’ CDs. As such, one of the more popular American genres produces somewhat lower numbers even among the services most attractive to its fans.

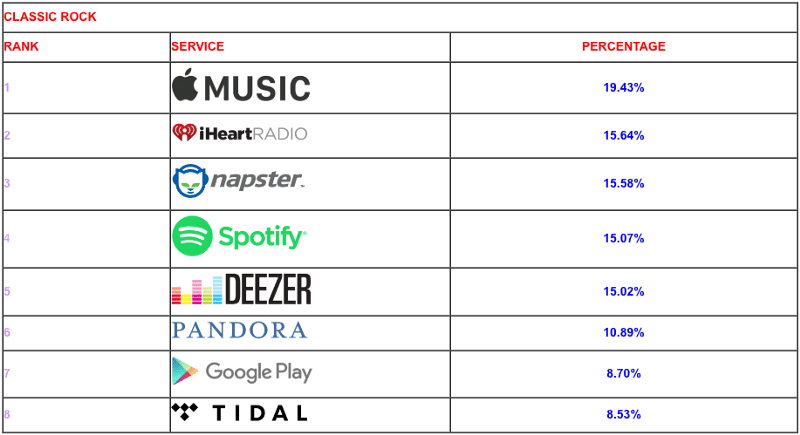

Classic rock’s numbers are low too, but it’s unsurprising that Apple tops the list rather confidently. iTunes always having done well with acts of that somewhat broad classification. While a lot of kids listen to what would theoretically be their parents’ music — in other words, kids still love The Doors, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and on and on — it is an album genre to a large degree.

While dominated by more contemporary acts, the current top downloads on iTunes do include Bob Weir’s new album, and greatest hits records by Creedence Clearwater Revival and Bob Marley.

Classic rock, however many units it moves (legitimately), is incredibly lucrative in the grandest scheme. As a genre, no other comes close in terms of concert tickets sales. At least not at premium prices. The 10 highest grossing tours of all-time are all from the 2000s, with the exception of one Rolling Stones tour from the mid-90s. The Stones have two tours on the list, the other their 2005–2007 world jaunt. U2 has two tours (and sorry to those who grew up in the 80s, but they’re considered classic rock now), there’s also a Roger Waters tour, an AC/DC tour, and the 2007–2008 reunion of The Police.

The other two are a Madonna tour from 2008, and a Cirque du Soleil tribute to Michael Jackson tour. Not classic rock, per se, but still from”your parents’ record collection,” as it were.

It may seem likely, perhaps, that TIDAL is the lowest ranking in this category.

Seven surprising minutes with the Geto Boys’ Scarface, in the video below, might change their minds, though. These things are all more connected than we make them out to be. Remember, a hardcore classical buff — particularly if they’re older — really can barely tell the difference between Run DMC and Led Zeppelin.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/6Czdg8e8UX4

Interestingly, entries two through five on the below chart are practically in a statistical tie, suggesting that the “classic” in classic rock is not there accidentally. This is stuff a lot of people listen to at least sometimes.

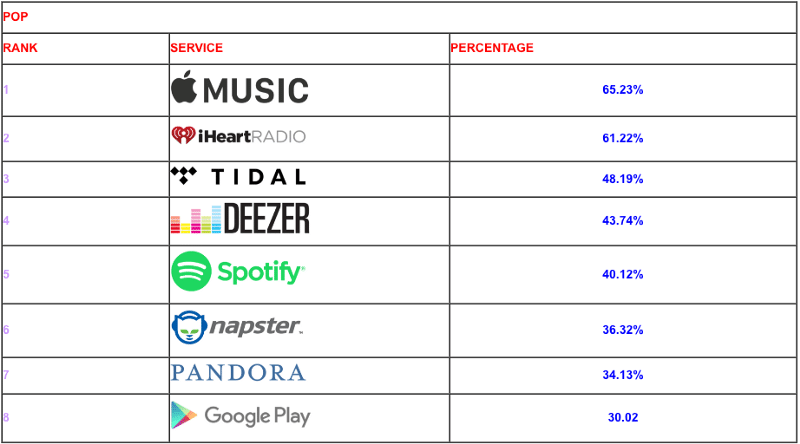

POP

Pop is a singles format, almost by definition (single is still a term that is used, even if no actual physical record exists). So, it makes well beyond perfect sense that the numbers here are large across the board. The next hit is just around the corner, and who can keep dropping that many dollars. And who wants to take up the storage on their phone, or laptop, with yesterday’s hits. Streaming keeps it fresh, and keeps you in the now.

iTunes has always done well with both album formats, and the pop hits of today. So, that Apple’s streaming service caters well to audiences on both sides of that fence makes sense.

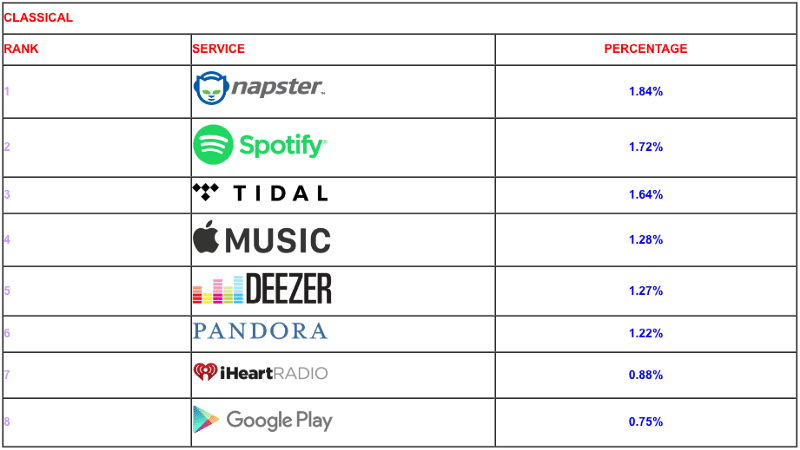

CLASSICAL

We did not gasp at the sight of such low numbers for the masters. Classical has not been a huge seller for many a decade, but those who are its fans are far more likely to purchase records or CDs, or listen to terrestrial or satellite radio.

The differences here are negligible, but the former Rhapsody, now branded as Napster does win the race. Making them, with their nearly 2%, the classiest of the streaming services.

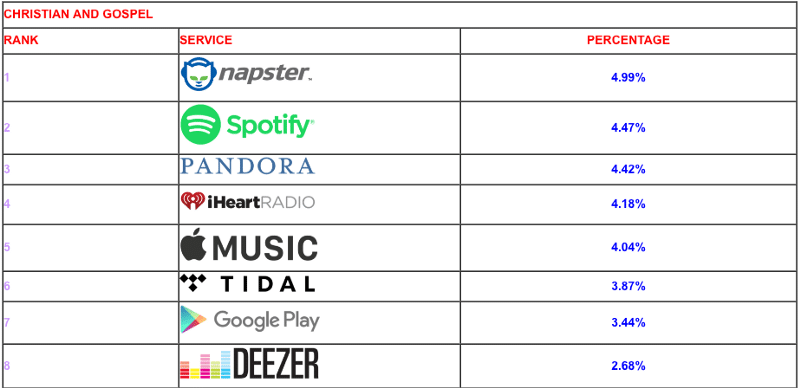

CHRISTIAN AND GOSPEL MUSIC

Again, Napster (the former Rhapsody) wins in a category that’s a bit more niche. However, quite lucrative. Christian pop, rock, rap, and traditional gospel all sell concert tickets, and even routinely move CDs in the six figures.

It’s a specialized area, but by it’s very nature devoted.

It’s worth noting that here and classical are the first times that we’re seeing Spotify — the theoretical king of streaming — near the top of one of these lists.

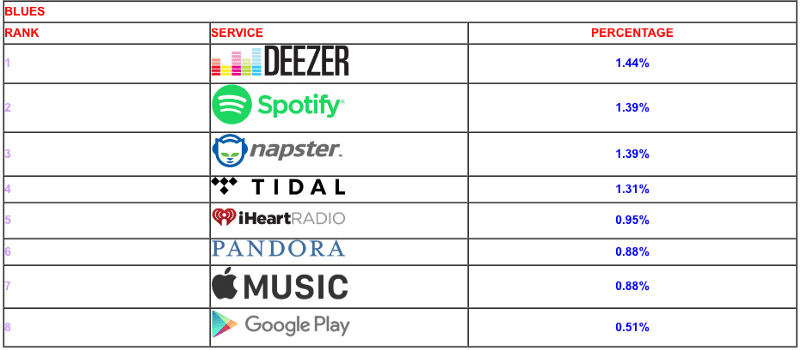

BLUES

“Deezer?” you might be heard to ask. Deezer is a French service with over 16 million members, 6 million of whom are paid subscribers. So, it’s a major player in this marketplace.

The blues, however, is seemingly not a major player in the world of streaming music, as the tiny numbers indicate. Still, 16 million users.

So listen bluesman, if even a tiny fraction of their users are listening, I know your lady done left you, but turn that frown upside down.

And again, in this more specialized area Spotify find themselves near the top, in a virtual statistical tie with the French victor.

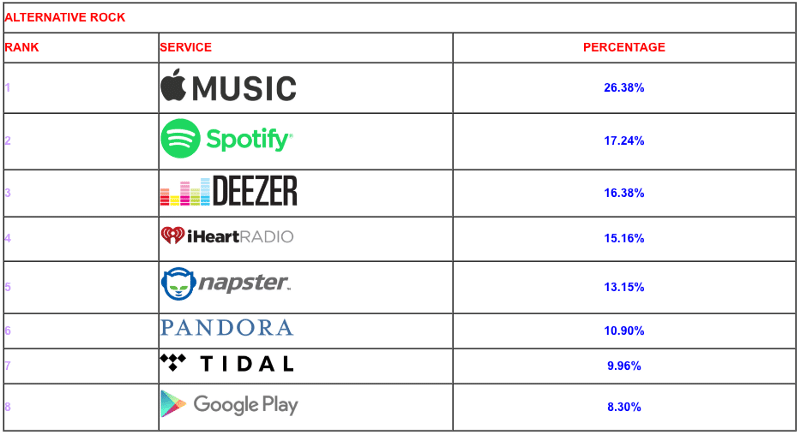

ALTERNATIVE ROCK

Alternative Rock, format-wise is a broad umbrella these days. It includes all the old school 90s groups — your Nirvanas and Pearl Jams (the latter of whom are still quite active, and quietly huge), or even older groups like your Jane’s Addictions and REMs. It also encompasses active bands like Radiohead, Muse, Arcade Fire, Coldplay, Foo Fighters, and groups that refuse to break up — no matter how hard you pray — like the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

U2, who we just called “classic rock” above might slip in here as well.

Genres like Alternative Rock and Classic Rock are more artist oriented, and therefore will do better with the album oriented services such as Spotify, and of course Apple Music which tops this list.

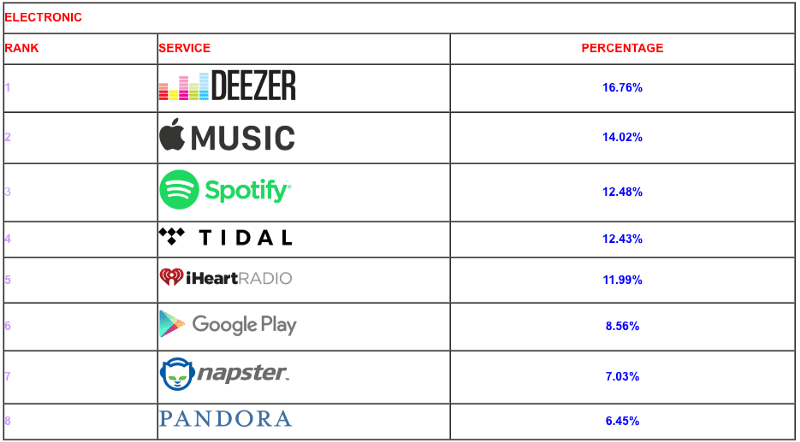

ELECTRONIC

Deezer’s European roots, and large European membership, make their first place finish here — as electronic music has been huge in Europe for decades — a natural. Apple Music and Spotify are not surprising either, as acts who “perform” what we’ve come to call EDM sell out arenas.

EDM, if you don’t know, is a catch-all phrase for “Electronic Dance Music.” Obliterating the hundreds of genres that fall under that umbrella, among its serious fans, EDM is a watered down, weekend warrior hybrid of techno, drum and bass, and especially the populist big beat genre. It’s just a big, dumb mish-mash of all the real electronic dance genres that came along in the 80s and 90s.

In the U.S. it’s primarily listened to by those that have come to be referred to as “bros,” which given techno’s largely gay and black origins is quite amusing.

But you’ve likely seen the footage of nameless DJ after nameless DJ play forgettable tracks to outdoor audiences of about 100,000 really good looking people. Many of whom are likely experimenting in one way or another.

These festivals do tend to have spectacular light shows and pyro. It’s just a shame it’s wasted on such nonsense music.

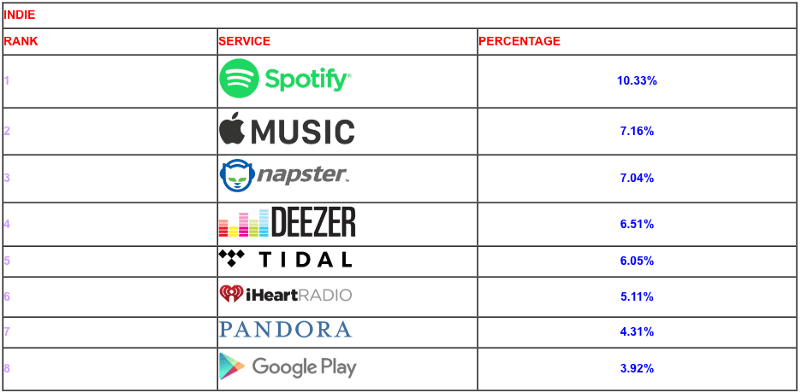

INDIE

How does Indie vary from Alternative Rock? Well, while there’s always been some cheating when using the term, it should mean the artist records for an independent label. Which, these days, means a label not owned by Universal, Sony, or Warners (as it’s played out over the decades, in 2016 all major labels are owned by one of those three companies).

But labels like Matador, Drag City, Sub Pop, and the largely folk/bluegrass focused Rounder Records would all count, as well as a vast many smaller labels.

Acts with significant international followings such as Ariel Pink, Deerhunter, Future Islands, The National, Cat Power, Belle and Sebastian, Interpol, Beach House, The Postal Service, Sleater-Kinney, Bon Iver, and Yo La Tango (and we could easily go on) all record for independent labels. We suspect a major label act or two might sneak into the format, but they’re not necessary.

Here, finally, Spotify tops the chart, and rather confidently too. Again, I think the album and artist orientation emphasized on Spotify makes them more appealing to fans of genres that revolve around such old fashioned notions.

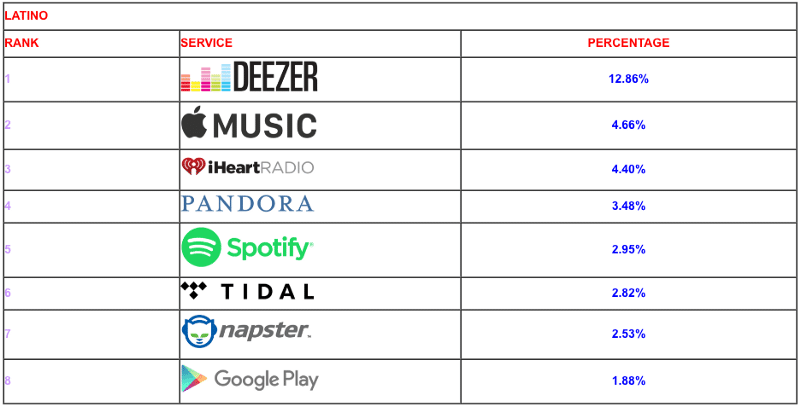

LATINO

Latino is a rather broad term. “Spanish language music,” that can incorporate traditional Salsa (a genre of mostly American origin, in fact invented in StatSocial’s beloved hometown), Salsa Romántica, Reggaeton, Bomba, Tejano, and literally hundreds of other genres.

But again, the international Deezer topping the list makes perfect sense. Apple’s second place finish is miles behind.

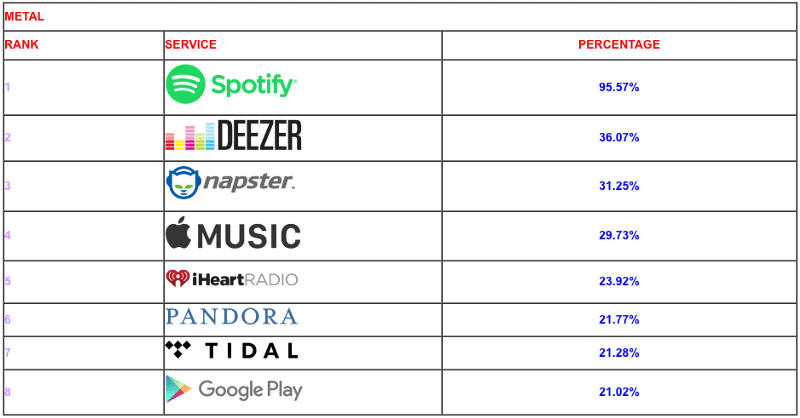

HEAVY METAL

No genre shy of Country (and possibly Hip Hop) has a more dedicated fan base than metal. Spotify’s huge, dominant numbers here suggest they have this locked down. You may laugh, but this is a very good genre to own.

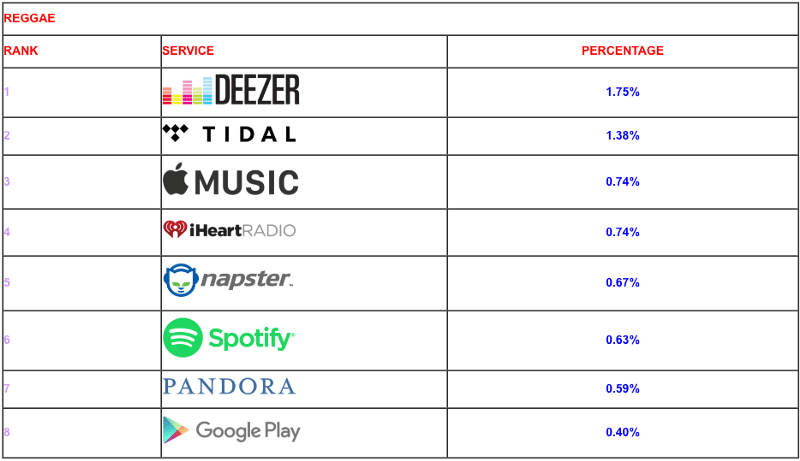

REGGAE

Deezer’s international audience again makes their slight victory here a natural. Jamaican music, particularly genres such Ragga, Dancehall, etc., are both similar and influential to Hip Hop, so the crossover in fans suggested by TIDAL’s occupying the second slot — surely given how relatively small the numbers are — makes perfect sense.

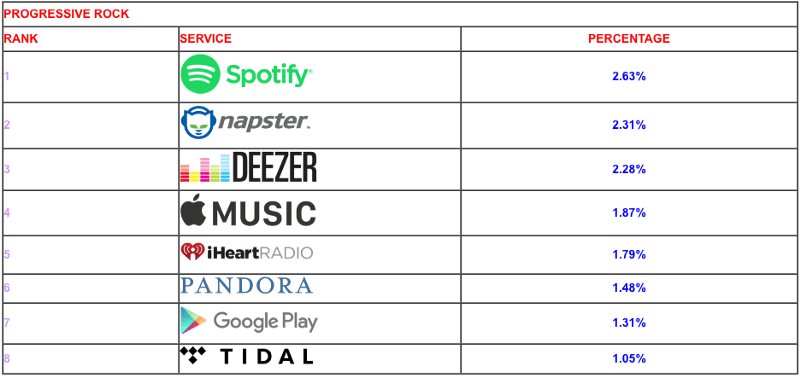

PROGRESSIVE ROCK

While we can joke about how Spotify also lives in its mom’s basement, and plays D&D. Or how it lives in its mom’s attic, and stares at its blacklight posters, under one influence or another. This genre’s fans are dedicated and lifelong, and again it is an artist and album oriented format. This seems to be where Spotify is strongest.

If this was progress, I’m glad things stagnated, or even regressed. But hey, what do we know? We’re not a music blog after all.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/qZquiACzPLY

And our statistics say that ELP are somewhere within the top 2,000 acts with Spotify’s social media audience. That may not sound so impressive, in fact it may not even be that impressive, but it’s probably higher than your band (unless you’re in Pink Floyd or 5 Seconds of Summer, or something).

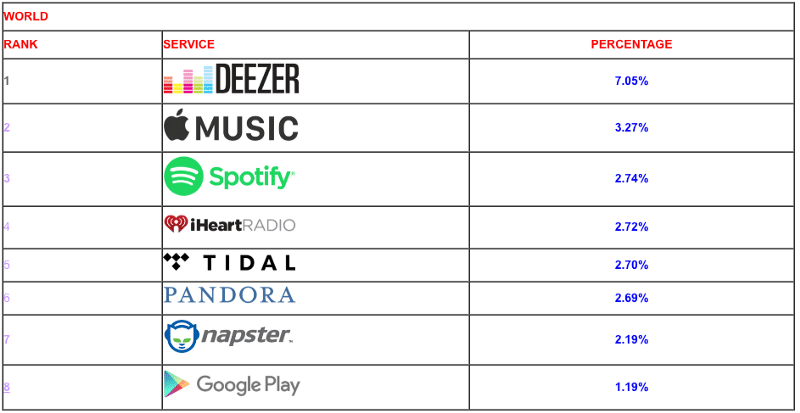

WORLD

World Music is such a dated term. But it’s still a format. It seems to simply mean music from anywhere other than North America, Europe, Australia, or the Caribbean.

African and Indian pop music dominate this genre, and South American music — particularly from Brazil — is also big. But the term is so broad as to be a bit meaningless.

Nonetheless, again, the particularly international Deezer comes out on top, which makes perfect sense.

And what was that we hinted at above? Was that talk of where an individual act ranked, in terms of being members of a streaming music service’s social media audience?

Well, the future may very well hold such entries, and such data may be thrust forth into cyberspace. Will you be here to witness it? Bookmark this page, and now go click the links below — if you’ve not done so already — and learn way more about us and what we do.

— –

To learn much more about StatSocial, the curious are encouraged to visit the StatSocial site itself, where you’ll find all sorts of stuff including sample reports.

— –

If you like what you’ve read, please take a few minutes to watch this overview of StatSocial’s data: